Much like the shifting shorelines and water levels of the lake itself, the history of Tulare Lake has remained difficult to map.

“The lake has a mystique,” said local historian Michael Semas. “There is a desire to know more. I think the mystery has always intrigued everybody.”

With the resurgence of Tulare Lake for the first time in more than a quarter of a century following a historically wet winter that left Kings County soggy and flooded, the history of what was once the largest body of fresh water west of the Mississippi River is again being embraced — not just for what it can tell us about the past — but about the present, and future.

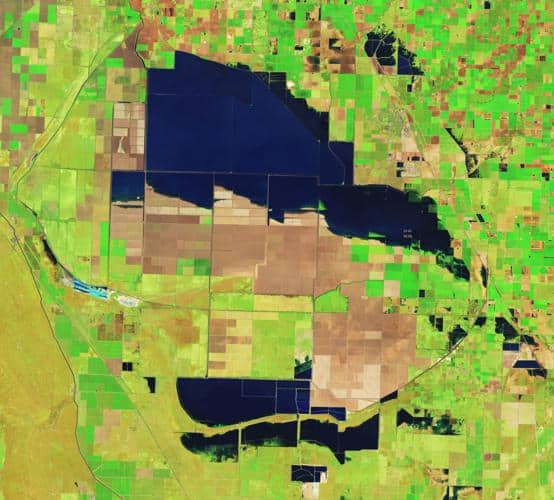

Road closures, submerged farms and NASA photographs confirm that on some level, Tulare Lake has returned, and local authorities and farmers are waiting to see how much worse the flooding will get.

The thawing of a record-breaking snowpack in the Sierra Nevada, dubbed “the big melt,” is projected to fill the Tulare Lake basin this summer with 1 million acre feet of water.

Like the lake’s resurgence this spring, its history is one of rapid change.

“Unfortunately, [Tulare Lake] changed so fast that we don’t have many detailed descriptions on what it was like in its early state,” College of the Sequoias professor Rob Hansen told Huell Howser during a 1999 episode of “California’s Gold.” “There was never any thorough study of the lake.”

The lake, at its largest, covered about 1,800 square miles of the Valley. From its northernmost point at Summit Lake, near Riverdale, to its southernmost point — generally about five miles north of what is now Wasco-Lost Hills Road — it spread over about 60 miles.

East to west, the lake’s waters would span the 35-mile stretch from what is now Kettleman City to Pixley.

If the lake were to suddenly reappear as it once was, Lemoore and Kettleman City homeowners would have lakefront property, Alpaugh would be an island, and Corcoran would be under water. In its heyday, the lake was wide and shallow, with most areas around seven feet deep — at the deepest it was nearly 30 feet, with a threshold of about 210 feet above sea level.

The lake was difficult to map and even more difficult to build permanent settlements around. Local historian and newspaper columnist F.F. Latta wrote that the heavy Valley winds could reshape the shoreline by up to five miles in a couple of hours. […]

Full article: hanfordsentinel.com

Clean water is essential for life, yet millions of Americans unknowingly consume contaminants through their…

Human brains contain higher concentrations of microplastics than other organs, according to a new study, and the…

From the Office of the Governor: In anticipation of a multi-day, significant atmospheric river in Northern California,…

From Governor Newsom: Scientists, water managers, state leaders, and experts throughout the state are calling…

Photo: A harmful algal bloom in Milford Lake, Kansas, made the water appear bright green.…

An expanded plastic foam coffee cup is at a donut shop in Monterey Park, California.…