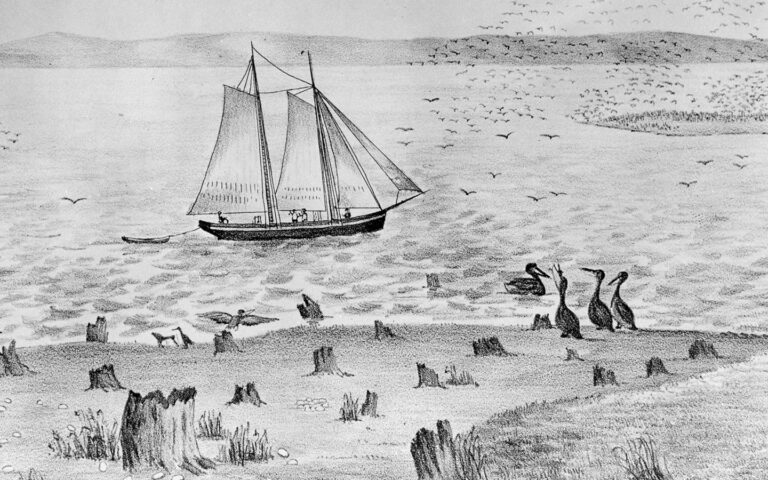

Art: An artist’s 19th century depiction of Tulare Lake, now vanished. (Tulare County Library)

…then we sucked it dry.

Fly above California’s Central Valley and a vast earth-toned checkerboard spreads out below. The fertile plain — as big as Tennessee and bathed in sunlight 300 days a year — yields a third of the produce grown in the United States. In his book “Coast of Dreams,” the historian Kevin Starr described the birth of the irrigated culture as “an imposition of will.” He wrote, “Across a century, great public works, ferocious machines, and the back-breaking labor of millions now forgotten had brought into being a place that nature never intended.”

Before the 1848 discovery of gold triggered a stampede of settlers into the state, the Central Valley was endowed with a watery landscape now hard to comprehend: dense riparian forests, swampy marshes, grasslands crowded with elk and pronghorn. Tulare Lake, between Bakersfield and Visalia, was the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi, with a surface area four times that of Lake Tahoe. In wet years, it was possible to sail from the lake all the way to San Francisco.

A century and a half later, California draws roughly half of the water out of the state’s environment. Of that, some 80% goes to agriculture.

There are 1,526 dams across the state, including hundreds along the western slopes of the Sierra, where a circulatory system of rivers fans out across the valley below. In the past, when the water ran wild, about 6,250 square miles of wetlands filled the Central Valley. That figure is now less than 350. Cut off from its tributaries, Tulare Lake vanished. A century of groundwater pumping has caused parts of the valley to drop 30 feet. The whole region seems […]

Full article: California’s Central Valley was once a watery landscape of lakes and marshes. Then we sucked it dry.