An Interview with Dr. Laurel Larsen, the Delta Stewardship Council’s Former Lead Scientist

Since the turn of the century, there has been a Delta Lead Scientist. Created in the year 2000 under the bygone program CALFED, the post signaled a new resolve: to give science a voice in the circles governing Delta affairs. Since 2009 the role has been a function of CALFED’s successor, the Delta Stewardship Council.

Sam Luoma, the first Lead Scientist, recalls a heady time, full of discovery and improvisation, when money flowed freely and large decisions about the Delta seemed just around the corner. His immediate successors had a more sobering experience as the CALFED energy waned. The fourth Lead Scientist, Peter Goodwin, consolidated the job in its new slot under the Stewardship Council, getting an ambitious Delta Science Program up and running. The fifth, John Callaway, had notable success in putting the program’s funding on solid ground. The sixth, Laurel Larsen, has just ended her stint. On her last day on the job, I asked her what she has learned about the role she played and the amazing place that is its focus.

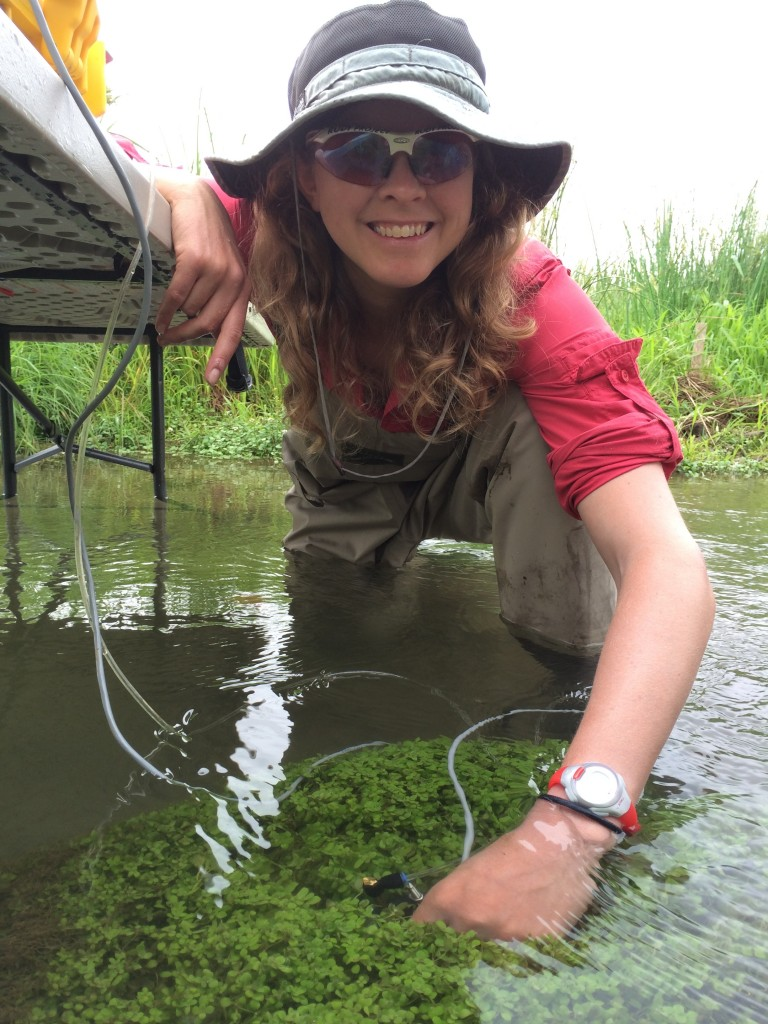

Like her predecessors, Larsen brought impressive credentials to the post. Among other roles, she headed the Environmental Systems Dynamics Laboratory at U.C. Berkeley. “We liked to deal with so-called ‘wicked problems,’” she says: complex and intractable messes, like the Delta. “That’s one reason that this position was attractive to me.”

Dr. Larsen feels that she arrived at a good moment. After a decade of settling in, the Delta Science Program had reached firm footing. Like Dr. Luoma at the beginning, Dr. Larsen felt a new freedom to reach out to the “brain trust” of scientists working on these problems, both in other agencies and on university campuses. “We are a boundary-crossing organization,” she says proudly. “One of my favorite parts of the job has been the inter-agency work. For instance, are we all using the same projections about climate change and sea-level rise? And I’ve been passionate about forging collaborations with academia.” (She has encountered criticism about the closeness of some of these collaborations.)

Another kind of boundary she hoped to cross was the one between the physical and the social sciences. Here, she says, she found herself pushing on an open door: the “tremendous dearth” on the sociological side was recognized in all quarters. “Resiliency is by and large a social problem,” she says. She points to the ongoing struggle to reconceive water rights. And Larsen, the first woman in her post, welcomed the recent emphasis on hearing formerly silenced voices: “Science does need to be more inclusive.”

During her term she has noticed more calls from sister agencies seeking […]

Full article: mavensnotebook.com