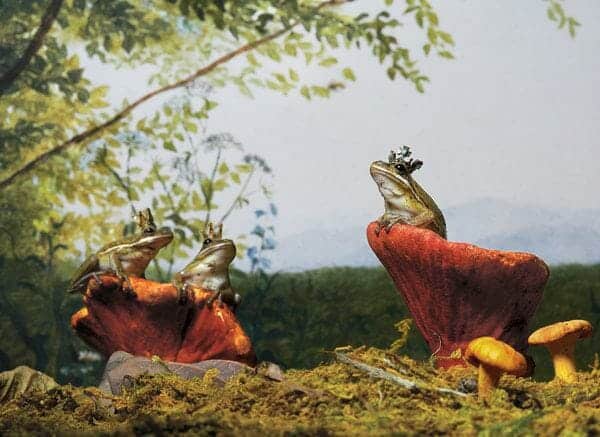

Banded bullfrogs, native to Southeast Asia (and not yet endangered), on their thrones of chanterelle, lobster and shiitake mushrooms. Photograph by Kyoko Hamada. Styled by Victoria Petro-Conroy

The dusky gopher frog, once endemic to the longleaf pine savannas of Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana — and now listed among the 100 most endangered species on earth — is tiny, dark and warty. The creature is often described as both secretive and shockingly loud, with a rumbling, back-of-the-throat mating call that is uncannily close to the human snore. It hides from the sun almost its whole life, finding shelter in burned-out tree stumps.

And although it’s armed against danger (its glands secrete poison), in the presence of a predator, the three-inch-long frog lifts its front legs to cover its eyes, like a child pretending to be invisible: You can’t see it if it can’t see you.

As of 2015, around 135 dusky gopher frogs were estimated to remain in the wild, mostly at a single pond in Mississippi, their breeding sites fragmented by new roads and the timber industry. The fate of the species may lie in the hands of the Supreme Court, which, as it begins a new term in October, will consider as its first case Weyerhaeuser Co. v. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. The lawsuit concerns the government’s designation of privately owned land in Louisiana as a critical habitat for the endangered frogs, setting property rights (and a potential $34 million loss in development value for the $27 billion Weyerhaeuser Company) against environmental conservation.

One study estimates that since the 1970s, around 200 frog species have disappeared, with a projected loss of hundreds more in the next century. Frogs are under threat on nearly every continent: from the French Pyrenees to the Central American rain forests to the Sierra Nevada in California. Some species, like the dusky gopher frog, have been depleted by human encroachment on their habitats. But the decimation that started 50 years ago was largely the work of the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, which thickens a frog’s skin, hindering the animal’s ability to absorb water and oxygen and to maintain a balanced flow of electrolytes, leading to heart failure. Once infected, entire populations can collapse in a single season.

No one knows exactly how the disease spread, but it was likely carried unwittingly by humans from one country to the next, or by the female African clawed frogs that were shipped around the world for laboratory experiments and, until the early 1970s, hospital pregnancy tests. (In the test, a frog was injected with a woman’s urine, which, if she was pregnant, would contain an ovary-stimulating hormone that caused the frog to lay eggs.) Live frogs, potential carriers of the disease, continue to be moved across borders into nonnative habitats; in the first decade of the 21st century, the United States imported nearly 48 million pounds of them, some destined to become exotic pets, others winding up on dining tables.

More than three billion frogs are eaten worldwide each year, some 4,000 tons by the French and half that by Americans, who tend to prefer them patted with flour and sautéed in browned butter. These are mostly farmed frogs and thus not as vulnerable to extinction, but the circumstances in which they’re bred and exported may contribute to the spread of disease. And while in some parts of Asia the whole frog — minus the skin, which contains toxins — is submitted to […]

Full article: Frogs Are Disappearing. What Does That Mean?

More about frogs and extinction:

Lonely Bolivian water frog seeks mate on Match.com to save his species

Seabirds Return to Desecheo Island One Year After Restoration

Scientists Listen to Fish to Figure Out How to Save Them

First evidence of popular farm pesticides in drinking water