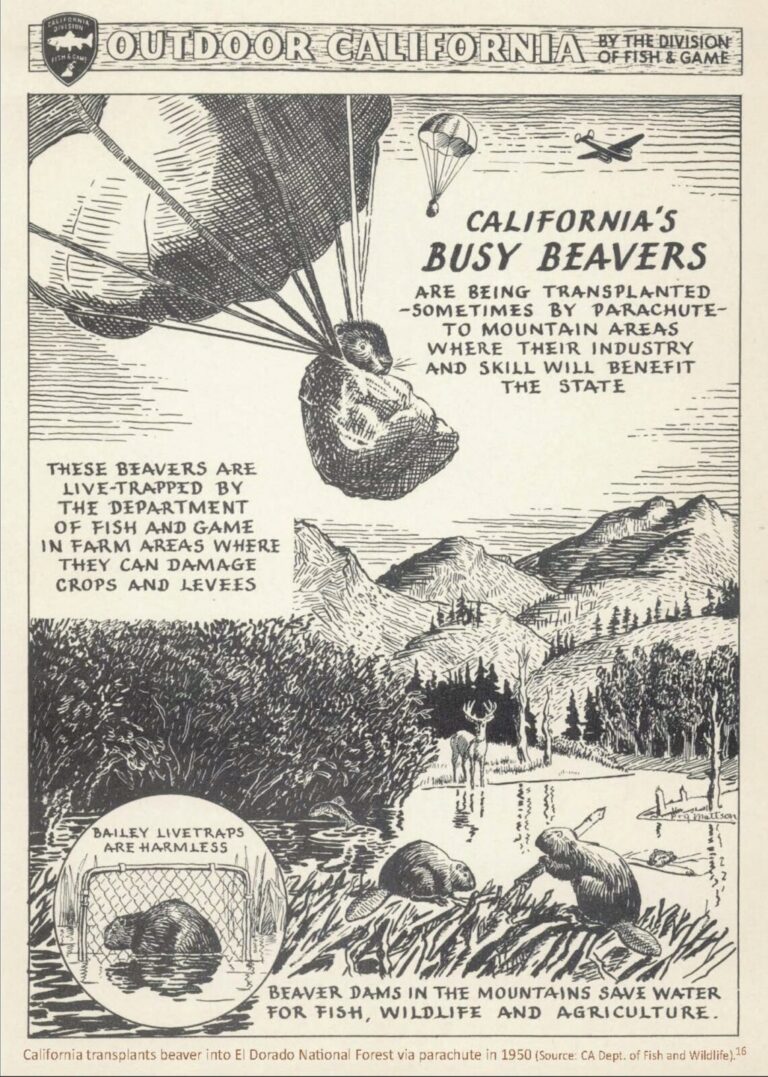

Art: A beaver poster from [CDFW’s] Outdoor California publication, 1950s. (Courtesy of California Department of Fish and Wildlife)

Inspired by the science of beaver wetlands, activists tackle a long-held belief that beavers aren’t native to much of California.

Last winter’s parade of atmospheric river storms raised water levels in the Bay Area’s creeks, rivers, and reservoirs. Like most water utilities, Santa Clara Valley Water District, which serves the county’s two million people, releases water from its 10 reservoirs ahead of big storms to make space for new runoff. The risk of unplanned flooding was close in January, when creeks were overflowing and Uvas and Almaden Reservoirs were spilling. In response, Valley Water released big flows from its Santa Cruz Mountain reservoirs, and the water rushed down Los Gatos Creek and the Guadalupe River out into San Francisco Bay.

As Steve Holmes walked along Los Gatos Creek beside Highway 17 in Campbell on a bright February day, not long after the emergency releases, he pointed out mounds of sticks and mud clinging to the banks. The director of South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition, Holmes has spent his decade in retirement clearing trash from streams in service to his love for fish. But another creature’s handiwork has also caught his eye over the years. We’re looking at the remnants of beaver dams blown out through a combination of stormwater runoff and Valley Water releasing its bounty. Trash clung to bushes several feet above the water, marking its peak height. “Do you think the beavers are still here?” I asked.

In recent years, beavers and their handiwork have been spotted in several Bay Area counties: Santa Clara, San Mateo, Contra Costa, Napa, Solano, and Sonoma, and according to a good bit of evidence, they have quietly lived in the Santa Cruz Mountains since the 1990s. Meanwhile, California introduced new policies in 2022 that embrace beavers as partners in supporting biodiversity, healing water systems, and reducing fires. This appreciation, spurred by the work of activists and scientists, is a shift from earlier state policies over past decades that by turns allowed beavers to be hunted for fur or killed as nuisance animals, then protected them, relocated them, and enabled them to be hunted again. Today’s beaver-friendlier approach will catch up California with other western states.

Beaver removal — and settlers cutting forests, straightening waterways, draining wetlands, and leveeing floodplains — altered the continent’s plumbing, speeding water off the land. Groundwater levels fell. North America became a drier, less ecologically diverse place.

Activists Kate Lundquist and Brock Dolman, founders of the Bring Back the Beaver campaign of the Sonoma-based Occidental Arts & Ecology Center (OAEC), have played a significant role in stoking beaver support, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The environmental advocacy and education nonprofit OAEC’s online guidebook Beaver in California: Creating a Culture of Stewardship, most recently published in 2020, lays out the animal’s history. Prior to Europeans’ arrival in North America, the authors note, there may have been anywhere from 60 million to 400 million beavers on the continent. In much of California, they were as numerous as anywhere.

Beavers are great swimmers but awkward on land, so they often build dams to create pools of water and dig canals, allowing them to harvest plants for food and construction across a wider area, safe from land predators. Historically, as much as one-tenth of North America was beaver-created wetlands. These, along with other wetlands, floodplains, meadows, and forests, played a critical role in the healthy water cycle.

Then came the commercial trappers, who hunted beavers for their dense fur, their castoreum (a glandular secretion) used in perfumes and medicine, and their meat. In the late 18th and 19th centuries Russian, European, and American fur traders were sailing the West Coast, trapping animals. By the early 1940s, California beaver numbers were thought to be as low as 1,300. Settlers who crossed the continent in the wake of trappers found newly dry, flat areas that seemed perfect for building and farming, rich with silt from millennia of water inundation.

However, something important had been lost in the West: reliable water. Beaver removal—as well as settlers cutting forests, straightening waterways, draining wetlands, and leveeing off floodplains—fundamentally altered the plumbing of the continent, speeding water off the land. Groundwater levels fell, no longer supplying streams year-round, and North America became a drier, less ecologically diverse place.

Parachutes, anyone?

Concerned that beavers might go extinct, the state in 1911 passed a ban on killing them. As beaver populations increased, the state allowed people to trap beavers to protect levees. A few years later, California loosened restrictions around possessing beaver hides. The resulting population crash led the state to protect them again in 1933. Nevertheless, some people appreciated beavers’ skills. Between 1923 and 1950, California relocated 1,221 beavers from towns, cities, and farmlands into more remote watersheds. Division biologist Donald Tappe explained why in a 1942 report: “It is now understood that soil erosion and shortage of water in some places resulted from the destruction of the beavers, which formerly built, and kept in repair, dams on the upper reaches of many streams. The dams were the effective means of impounding waters of the spring runoff, and of distributing them slowly downstream throughout the Summer.”

Idaho’s Department of Fish and Game had come to the same conclusion. Managers there, puzzling over how to move beavers into roadless areas, came up with a solution inspired by World War II airborne divisions: parachuting. In fall 1948, staff dropped 76 beavers in the Idaho mountains. Inspired, California wildlife staff also deployed beavers via […]

Full article: baynature.org