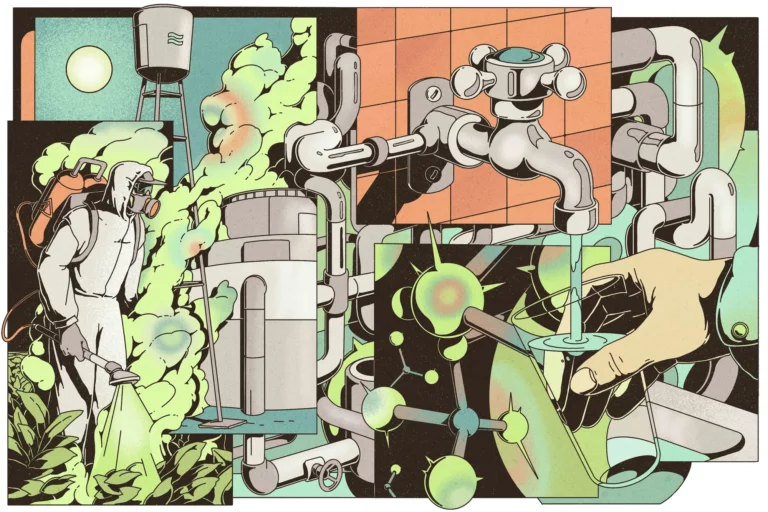

Credit: Illustration by Micha Huigen, special to ProPublica

The inaction on regulating contaminants — including those that likely cause cancer, reproductive or developmental issues — found in the water of millions of Americans illustrates shortcomings in the U.S. response to environmental threats, say experts.

As far as state and federal officials are concerned, the drinking water in Smithwick, Texas, is perfectly safe.

Over the past two decades, the utility that provides water to much of the community has had little trouble complying with the Safe Drinking Water Act, which is intended to assure Americans that their tap water is clean. Yet, at least once a year since 2019, the Smithwick Mills water system, which serves about 200 residents in the area, has reported high levels of the synthetic chemical 1,2,3-trichloropropane, according to data provided by the Environmental Working Group, an advocacy organization that collects water testing results from states.

The chemical, a cleaning and degreasing solvent that is also a byproduct from manufacturing pesticides, is commonly referred to as TCP. It has been labeled as a likely carcinogen by the Environmental Protection Agency for more than a decade. There have been few active sources of TCP since the 1990s, but its legacy lives on because it breaks down slowly in the environment.

How it got into the Smithwick Mills water supply is a bit of a mystery. There are some farms in the area, but it’s unclear whether they have used pesticides containing the chemical, and there are no known industrial sources nearby.

The TCP levels in the Smithwick Mills system are alarming to those who study water contamination. As with many chemicals, there’s limited information on TCP’s long-term effect on humans. But research involving animals shows evidence that it increases cancer risks at lower concentrations than many other known or likely carcinogens, including arsenic. Because of this, in 2017, California state regulators set a maximum allowable level for TCP in water of 5 parts per trillion. Water quality tests from the Smithwick Mills utility have revealed an average TCP level of 410 parts per trillion over the past four years — more than 80 times what would be allowed in California.

But the utility hasn’t taken any action. It doesn’t have to. The chemical isn’t regulated in drinking water by the EPA or the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, which means neither agency has ever set a maximum allowable level of TCP. It’s not clear why Smithwick Mills was even monitoring for the chemical, though state officials said […]

Full article: www.propublica.org